Dramatist, first great Greek tragedian. He expressed a tragic sense of life, which in modern terms may be equated with romanticism, and an appreciation of the truth as perceived through our emotions.

Statesman and general. His name became synonymous with ancient Greek ideals of male beauty. But in his military career, he betrayed his city, Athens, and was eventually assassinated.

King of Macedonia and conqueror of Persia. Some see in him the spirit of youth, daring, courage, energy, hardihood, curiosity, vision, and the intellectual and artistic heritage of ancient Greece, which he spread widely, together with a tolerance and appreciation of other cultures.

Others see drunkenness, superstition, cruelty, vindictiveness, violence, killing both on and off the battlefield, lack of self-control, despotism, and the age-old gods of power, wealth, fame, and glory pursued to the point of madness.

Poet. He was known for his satire and also for his love poetry.

Cousin and follower of the Buddha. She helped establish a Buddhist order for women.

Philosopher. His life expressed the value of scientific or at least pre-scientific curiosity, inquiry, and speculation. He was charged with religious deviance, and was forced into exile from Athens.

Macedonian Regent. Perhaps because he was forty-two years older than the young king, Alexander the Great trusted him sufficiently to name him Regent of Macedonia when he left on his campaign of conquest. His name is associated with loyalty and reliability.

Thinker and pupil of Socrates. He is credited, along with his own pupil Diogenes, with founding the famous Cynic school of Athens. (See Diogenes.)

Soldier. His career was marked by bravery and devotion to his kinsman Julius Caesar, but most famously by his passionate love affair (and alliance) with Cleopatra, the Greek Queen of Egypt. The traditional account holds that when Cleopatra fled with her ships from the naval battle of Actium, Antony foolishly followed her, thereby assuring the triumph of Octavian, later Augustus Caesar. An alternative possibility is that Cleopatra had her entire treasure on board and fled by prearrangement when the battle went poorly. In any case, Octavian pursued, and first Antony and then Cleopatra dramatically committed suicide. Antony has thus come to represent the heights of heroism and loyalty along with the perils of passion.

Scientist and engineer. He was a founder of hydrostatics, discoverer of mathematical descriptions of various shapes and figures, and inventor of many practical machines, including defense weapons. His life, work, and personality expressed the sheer joy of investigation, study, discovery, and knowledge. In one story, he leaps from his bath shouting "Eureka (I have found it)" after solving a problem and runs into the street.

Astronomer. His belief that the earth revolved around the sun illustrates the power of human speculation and inquiry, even when unaided by sophisticated equipment.

Grammarian and critic. In addition to helping preserve Homer, he helped develop philology, whose Greek roots mean love of words.

Soldier and statesman. Aristides was often referred to as "the just." The story goes that the Athenians were voting whether to exile Aristides (political leaders were often exiled or "ostracized" for a time to limit their power and to ensure the survival of the Athenian democracy). One commoner, not recognizing the statesman, asked him for assistance in voting against him. Aristides helped him without demur.

Philosopher. He lived in Athens, but was born in Cyrene in North Africa. Hence his philosophy was referred to as Cyrenaicism and his followers as Cyreniacs. Unlike his master Socrates, Aristippus unashamedly charged his pupils whatever the traffic would bear and by his own profession lived as extravagantly as he could.

Although no work of his survives, Cyrenaicism taught an unalloyed and unrepentant hedonism, with immediate pleasure (very much including physical pleasure) to be pursued, pain avoided, and other objects and ends of little account. But one should approach the pursuit of pleasure with a rational mind and a degree of self-control or pleasure will too easily turn to pain. As Aristippus said of an expensive female companion, "I have Lais, not she me."

It will be apparent that Aristippus's advice to give free rein to desires, to pursue pleasure without remorse, but not to fret over much when desires are thwarted, is actually quite difficult to follow, which ultimately limited its appeal.

Cyrenaicism was sometimes confused with Epicureanism, but in the latter pleasure is defined very differently as a calm, undisturbed mind supported by good physical health, not by physical enjoyment or luxuries.

Dramatist. He was a master of comedy, satire, and especially political satire.

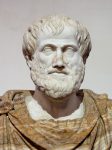

Philosopher, pupil of Plato, and tutor to Alexander the Great. His work ranged widely over logic, metaphysics, physics, biology, zoology, natural history, history, politics, rhetoric, moral philosophy, psychology, and poetry.

Although his most important works perished, enough survived, principally through Arab sources, that he became the greatest secular authority of the late Medieval and Renaissance world, so much so that for a time his commanding presence stifled further investigation and free thought. This was especially ironic because his surviving work expressed the value of free study and thought above all, both in the form of logic and especially of empiricism, of careful observation of the world around us, of a primary reliance on the evidence of our own senses and our own mind rather than on an external authority, no matter how masterful and prestigious that authority may be.

Aristotle's moral philosophy suggested that happiness should be our goal (Eudamonism), that virtue was a reliable means to this end, and that virtue usually represented a "golden mean" between opposite extremes. This approach to a happy life did not seem to require religion, especially the quasi-mystical religion of Plato, but it did require philosophical contemplation which in turn depended on financial independence or subsidy and the leisure that such independence or subsidy made possible. Supreme happiness was therefore reserved for the few.

Aristotle also emphasized the importance of friendship for happiness, all the more so since women and children were subordinate in classical Greece and thus less suitable for intellectual intimacy. (Montaigne felt the same way in Renaissance France, that psychic, as opposed to physical, intimacy should be reserved for close male friends.)

Other Aristotelian positions are equally rooted in the circumstances of his time, including his positive valuation of political autocracy and slavery. Although he probably regarded both as natural and inescapable, any opposition to autocracy during his lifetime would have been extremely dangerous and futile.

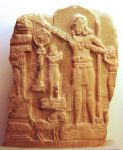

Mauryan King of India. After a conventional, ruthless, and successful military career dedicated to the pursuit of power and conquest, Asoka unexpectedly changed course. He converted to Buddhism and dedicated the rest of his life to useful public works and especially to the propagation of principles of non-violence, toleration, kindness (especially to slaves and inferiors), generosity, and charity collectively referred to as dhamma.

Asoka's new philosophy was circulated throughout the kingdom as a series of Edicts which were inscribed on large granite stones, some of which have survived.

Pericles's lover. She was an early exemplar of female independence and outspokenness.

Author. He is chiefly known as the recipient of Cicero's Letters to Atticus. Like Cicero, he was a person of deep culture and wrote histories and other works. As an avowed Epicurean, he wisely chose to leave Rome and its political disturbances during the years leading to the Empire. And when confronted with failing health and a painful end, he simply starved himself to death.

Political leader and soldier. Called the "noblest Roman," he helped to assassinate Julius Caesar in a vain attempt to try to save the republic.